El Profe: Do You Know Mr. Vázquez?

By Adrian Burgos

It seemed a simple question: Do you know Mr. Vázquez?

But that question and the person who asked was evidence that my baseball world and academic world had collided way before I even realized.

“Worlds colliding” was an abiding concern of George Costanza’s character on the 1990s comedy Seinfeld. He could not handle having individuals from his inner sanctum (friends Jerry, Kramer, and Elaine) interact with those from other parts of his life (his girlfriend or coworkers). “Anybody knows you gotta keep your worlds apart,” he screams at Jerry, or it’s chaos.

Interesting things happen when worlds collide, when you become aware of how interconnected one’s social and professional circles already are.

We often talk about six degrees of separation before the digital age and social media—that everyone on the globe is six steps away from each other through who we know.

In some of our circles, it seems that there are even fewer degrees of separation from knowing one another. This seems especially the case when one does research on Latinos in baseball with a particular focus on those who played in the Negro Leagues.

Latinos who played in the Negro Leagues were not particularly numerous. About 250 Latinos participated in the Black baseball circuit between 1900 and the 1950s. The number of surviving players was significantly smaller when I started my research in the 1990s.

Baseball Life

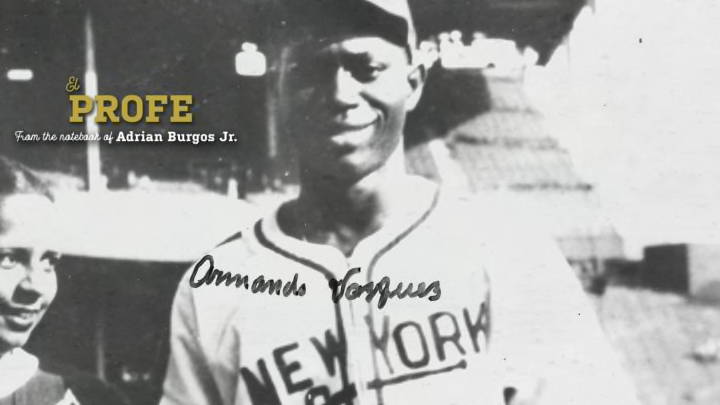

Armando Vázquez was among the first Latinos who played in the Negro Leagues who I interviewed in the mid-1990s. He was living in upper Manhattan on the west side and just south of Harlem when we first met.

To meet Vázquez was to never forget you had met him. His voice and laughter could fill a room. He loved to compartir, to sit around and talk about this and that for hours. Among the things I enjoyed about his company was that he could easily flow from storytelling with colorful language in Spanish to doing so in English.

A native of Güines, Cuba, Vázquez started playing professionally in Cuba before he headed to the United States in 1944 to play with the Indianapolis Clowns. During World War II, the Clowns did the same thing the Washington Senators in the major leagues did. They turned to Latin America and particularly Cuba for players to fill their roster.

After two seasons with the Clowns, Vázquez joined the New York Cubans as a reserve infielder, primarily playing first base. The left-handed hitting Vázquez possessed enough talent and was still considered young enough to be among those Negro Leaguers to play in integrated leagues, first in the Manitoba-Dakota League, where he played three seasons. He returned to the barnstorming Indianapolis Clowns in 1952 and then spent a season in the minor leagues in 1954.

After Baseball

Like most Negro Leaguers, Vázquez had to pursue a second livelihood after retiring from being a professional ballplayer. Unless you were Satchel Paige, Josh Gibson, and another major star, you really didn’t earn much money in Black baseball or in the minor leagues.

Vázquez also faced a different question after his playing days ended. Would he return to his native Cuba or remain in the United States? It wasn’t an easy choice for the Afro-Cuban who had dealt with Jim Crow segregation throughout his playing career in the States. That question became even more difficult in January 1959 when Fidel Castro took power in Cuba.

Vázquez opted to settle in New York. Others decided to go back. Such was the case of his then close friend Edmundo “Sandy” Amorós. Seven years younger than Vázquez, Amorós had enjoyed a more successful professional career, making the transition from the Negro Leagues to the majors, where he had a seven-year career primarily with the Brooklyn Dodgers. The Cuban outfielder’s famous running catch in Game 7 of the 1955 World Series versus the Yankees helped secure the Dodgers’ first World Series title. The decision to return to Cuba would separate the two friends and put them on different paths.

Checking in With Mr. Vázquez

After graduating from college I spent a year as a teaching fellow at an alternative high school in Spanish Harlem—ironically located in the Jackie Robinson Education Complex. The master teacher for our fellows program was an education professor, Claritha “Peaches” Osborne. A native Harlemite, she seemingly had mentored teachers at every school across Harlem and Manhattan.

During one of my research visits to the Schomburg Center for Research on Black Culture in Harlem, I dropped in to catch up with Peaches, who insisted I not call her Ms. Osborne. In addition to providing family updates we also discussed my latest research on Latinos in baseball. Then she asked whether I knew the man who worked on the custodial staff at PS 163 on 97th Street. He was an older Cuban man who she had heard had played professional baseball many years ago.

“What’s his name?” I asked.

“Mr. Vázquez,” she replied.

Her description of his personality and particularly his voice and laugh assured me we both knew the very same Armando Vázquez I had interviewed several times and had hung out with even more.

We swapped stories of our interactions with Vázquez over the years, hers at the school and mine at Negro League gatherings and at his Manhattan apartment. We talked about the many Afro-Cubans who had settled in the lower end of Harlem in the early 20th century that it became known as Little Ybor after the section of Tampa, Florida from which they migrated. That Cubans and Latinos were always part of the Harlem she knew since the 1920s.

My worlds had collided years during the years I knew them both and before, and nothing bad happened. Perhaps George Costanza’s theory was a bunch of bunk after all.

Featured Image: La Vida Baseball