El Profe: Negro League Beisbol exhibit illuminates an important history

By Adrian Burgos

Long before Shohei Ohtani made his debut in Major League Baseball for the Los Angeles Angels, there was Martin Dihigo in the Negro Leagues. Dihigo might well be the greatest two-way player that most baseball fans have not heard of because he played during baseball’s segregated era.

Inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1977, Dihigo was the first Latino enshrined as a Negro Leaguer. The Cuba native came to the United States in 1923. His hitting prowess, strong build, and powerful arm impressed Cuban Stars owner Alex Pompez, who decided to bring the 18-year old north to play in the Eastern Colored League.

Over the next three decades, Dihigo demonstrated great versatility while performing in the Negro Leagues and throughout Latin America.

Dihigo was a pitching ace. He won over 200 games combined pitching in the Negro Leagues, Mexican League, Cuban League and other Latin American leagues. He was also a power-hitter who excelled in the field. While he started as a second baseman in 1923, he would play every other position except for catcher during his professional career.

That combination of stellar performance and versatility resulted in Dihigo being elected by a special committee on the Negro Leagues to enter the Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, N.Y. Dihigo was also enshrined in the baseball halls of fame in Mexico, Cuba, Venezuela and the Dominican Republic.

A statue of Dihigo also stands in the Field of Legends at the Negro League Baseball Museum in Kansas City.

Illuminating stories like that of Dihigo and of Latinos in the Negro Leagues is a central purpose why the NLBM created the Negro League Béisbol exhibit.

A Baseball Haven

Some baseball fans are aware that just over 50 foreign-born and U.S.-born Latinos played in the majors from 1902 through 1947, before Jackie Robinson started the integration of baseball.

Fewer fans know that over 240 Latinos participated in the Negro Leagues during that same period. The Negro Leagues were a baseball haven for these talented ballplayers, giving them a stage where they could perform all summer long before participating in the winter leagues in the Caribbean and Latin America.

The Black baseball circuit in the United States welcomed all Latinos, regardless of color, during the era when a color line ruled in MLB. Even before a formal Negro League was established in 1920, Cuban teams participated in the Black circuit starting in the early 1900s. Just as significant, teams in Cuba’s winter league recruited African American players during that same decade.

That history of baseball exchange between Latin America and African Americans is the focal point of Negro League Béisbol.

A Unique History

The Negro League Baseball Museum is dedicated to telling the story of Black baseball from its earliest days through its vital role in the transformation of U.S. professional baseball.

Part of the Negro Leagues’ legacy is the important role the leagues had in providing talented Latinos a circuit where they could regularly participate in the United States.

The Negro Leagues also had Latino-owned teams, Latino managers, and Latino umpires, all decades before the majors did.

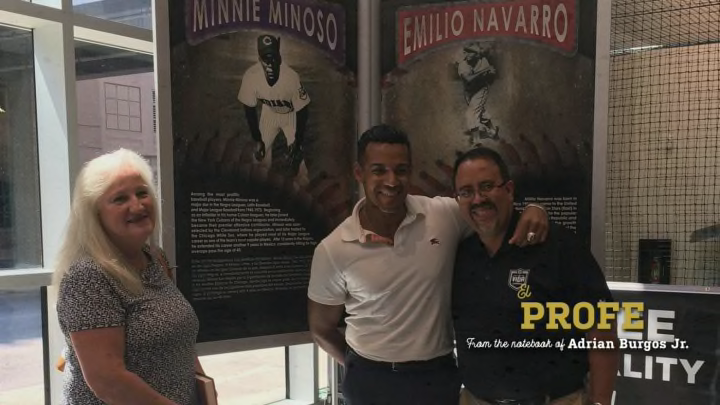

In 2014, the NLBM officially opened its Negro League Béisbol exhibit to tell this unique history. Initially at the Kansas City-based museum, the exhibit is now a traveling one that is currently being housed by the Chicago White Sox at the Chicago Sports Depot through September 26.

Telling a Béisbol History

Dr. Raymond Doswell, executive vice president of the NLBM, spoke about the museum’s efforts to highlight the important role of the Negro Leagues through this exhibit.

“The Latino community is an important one to the NLBM,” he said. “The museum wants everyone to know that their heritage, through baseball, is reflected here.

“The roles and connections of the Negro Leagues to Latino culture is one of those stories worth exploring in more detail.”

While it is certainly a history worth knowing, there were challenges in creating an exhibit that highlighted this unique history. Many of the key figures involved in this history died long ago. Similarly, decades have passed since the Negro Leagues ended.

The NLBM, which was founded in 1990 and championed by Buck O’Neil, has been collecting artifacts and oral history of players, umpires, and league officials.

“Fortunately, the museum had a lot of unique and important material it could present, so it made visuals relatively easy to pull together,” Doswell noted.

“Most important, the museum also had the materials (photographs, posters, stories, film) to make an impactful and robust presentation,” he said.

Learning Beisbol History

Entrusted with curating Negro League Beisbol, Doswell became even more knowledgeable about the participation of Latinos in the Negro Leagues and about the meaning that African American players attached to their time playing in Latin America.

“There was a competitive brotherhood between African American and Latino baseball players,” he said.

Creating the opportunity for current fans to learn about this history, to learn Beisbol history is what makes the Negro League Béisbol exhibit so important.

It allows fans to learn about José Méndez and his leadership as player-manager of the Kansas City Monarchs of the 1920s. They can also learn about the other Luis Tiant, the lefty ace who at age 42 was still a dominating pitcher for the 1947 New York Cubans that won the Negro League World Series. Fans can also learn about Tiant’s teammate, Orestes Miñoso who as a kid growing up in Cuba idolized a player nicknamed “El Maestro” and “El Inmortal,” Martin Dihigo.

Featured Image: La Vida Baseball