Dodging the Draft

By Adrian Burgos

On October 26, with Major League Baseball’s collective bargaining agreement nearing its expiration, Nelson Cruz, Edwin Encarnación and others took to social media.

They started posting and retweeting, taking a stance that departed from the expectations of how Latino ballplayers should act when it comes to labor relations matters. There was a flurry of different messages, including this one on Instagram from Cruz, the Seattle Mariners’ right fielder from the Dominican Republic who has hit 40 or more home runs the past three seasons:

“Hola, soy Nelson Cruz. Yo, como muchos otros dominicanos, peloteros, scouts y familiares, no estamos de acuerdo con el draft internacional ni con el cambio de edad”.

“Hi, I’m Nelson Cruz. Like many other Dominicans, ballplayers, scouts and relatives, I do not support an international draft or a change in (eligibility) age.”

Added his fellow Dominican Encarnación in a similar posting on Instagram: “It’s not in our country’s interest.”

In so doing, Cruz, Encarnación and a contingent of Latinos that included countrymen José Reyes and Gary Sánchez openly expressed their stance against the international draft, whether in the form of including foreign-born players in the amateur draft or a stand-alone draft of international prospects.

MLB owners and the Major League Baseball Players Association did rap out a new CBA — a five-year deal that staved off a lockout. And while management failed to obtain an international draft of amateurs residing outside the U.S., Puerto Rico and Canada, it successfully implemented a hard cap on the amount MLB clubs can spend annually on international free agents.

But since the start of the 21st century, the issue of an international draft has arisen each time a CBA has been negotiated, so it may be wise for the players to continue taking a strong stand. And though one battle has been won with the help of Cruz, Encarnación and others, the war continues as MLB seems to be squeezing salaries — especially those of young Latino players. The dollars are in a downward spiral. Take those hard caps, for instance.

A punishing decision

Under the old CBA, teams had varying limits on bonuses going to international amateurs. Then the Boston Red Sox blew away everyone when they signed Yoan Moncada of Cuba to a $31.5 million bonus. A boy wonder who attracted the attention of scouts at age 15, Moncada was given permission by the Cuban government to leave the island and pursue his dream of making it to the major leagues.

Boston ended up paying $63 million after figuring in the overage tax on the bonus, with a 100 percent tax of $31.5 million going to MLB.

Seeing the cavalier attitude Boston had toward the cap, MLB decided to turn the screw. Under the new CBA, teams will all carry the same limit — a hard cap of between $4.75 million to $5.75 million a year, depending on where you pick in the amateur draft. As Red Sox blogger Matt Collins tweeted, the new cap is 16 percent of Moncada’s signing bonus.

In the end, Latin American ballplayers – mostly young kids escaping great poverty – end up being penalized.

Is an international draft inevitable?

Owners have long wanted to transform MLB’s annual amateur draft, first instituted in 1965, into an international draft. Such a revision would expand the draft beyond the United States and Canada to include amateur prospects from throughout the baseball-playing world. Puerto Rico was included in the amateur draft in 1990, arguably affecting the flow of talent for a generation. MLB owners also favor implementing an international draft because it lowers the overall cost of initial talent acquisition and further swings negotiations with amateur prospects in the owners’ favor.

This past winter was no different, when MLB Commissioner Rob Manfred met with MLBPA Executive Director Tony Clark to negotiate their first deal in their new roles as lead representatives of owners and players, respectively.

The impact of such changes would be felt most directly in Latin America, the largest source of foreign-born talent for MLB and its minor league affiliates. Which is why the position Cruz, Encarnación and the other players took was significant and was framed by a distinctively Latin American perspective that linked the past, present and future of Latino baseball.

Latino ballplayers seen as passive

Since the late 1990s, big-leaguers such as Gary Sheffield have complained that owners and league officials preferred Latinos over African-Americans, working off the perception that Latino ballplayers prefer to keep the peace and are unwilling to collectively challenge owners.

In the minds of those complaining, owners could therefore exert more control over Latino players, particularly during their participation in the lower minor leagues, a time of singular vulnerability as they tried to understand the cultural expectations of baseball, and everyday life, in the U.S.

The latest push has proved different.

Latinos took the “passive” perception head-on. Players not only tweeted and posted on Instagram, they participated in the negotiating sessions. The willingness of Latino All-Stars to disrupt their offseason to fly in and take a stand to protect the interests of unsigned amateur prospects of Latin America made an impression.

It was a moment that made a difference, and one that surely made Felipe Aloú proud.

An early advocate

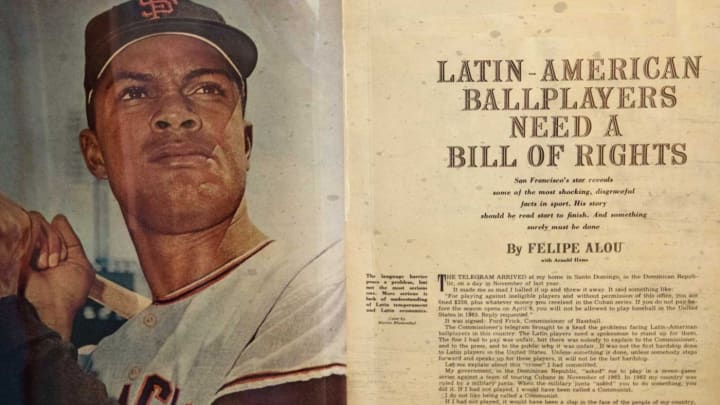

Part of the pioneering generation of black players who broke in during the 1950s, Aloú actively spoke out for his fellow Latinos. His frustration boiled over in 1963. Feeling that then-MLB Commissioner Ford Frick and other MLB officials failed to adequately address the particular plight of Latinos, Aloú co-authored with Arnold Hano a landmark article, “Latin American Ballplayers Need a Bill of Rights,” for Sport magazine. Aloú detailed the ways Latino players were affected by league rules and policies.

Among the grievances Aloú wrote about was his being prohibited by Frick from playing in goodwill games in his home country, the Dominican Republic, organized by the country’s recently elected president following a civil war. Frick took this stance because the proposed games would include Cuban players that had previously participated in the Cuban winter league, which MLB had deemed an outlaw league. All participants would be fined and suspended, Frick declared.

The seeming disregard the commissioner had for the particular situation of Latino players deeply upset Aloú. In his mind, what the inattention to the Latino players’ plight called for was representation and a clear declaration of rights.

Fifty-three years later, Latino players looked at the past and present of baseball in the Caribbean and sought to protect the future. The sporting press took notice as Cruz, Encarnación, Sánchez and others banded together in taking to Instagram, Twitter and other social media to express their opposition to the international draft.

Voices for the voiceless

Why were these Latinos willing to take a stand against the international draft? What are the stakes for those in the Dominican Republic, Venezuela, Panama and elsewhere in Latin America? (And, yes, Cuba presents its own set of issues; that is another discussion for another column).

An international draft would profoundly change the dynamics for Latino prospects when it comes to the power to choose and in negotiating a signing bonus. In the amateur draft, an MLB organization selects an individual player and thus secures exclusive rights to negotiate his contract.

Currently, however, MLB rules deem prospects from the Dominican Republic, Venezuela and other Latin American countries as amateur free agents eligible to be signed at the age of 16. As amateur free agents, these Latinos are able to negotiate with all interested MLB organizations to secure the best contract and signing bonus. This not only means there is more competition for the prospect’s services but that it is the prospect who gets to choose which organization he will sign with. Conversely, for those left undrafted in an international draft, there is considerably less leverage to negotiate with teams and secure a significant signing bonus.

Lessons from Puerto Rico

The warning signs of what being included in MLB’s amateur draft can mean for Dominicans and Venezuelans are clear when one considers what happened in Puerto Rico in the 1990s. After MLB decided in 1989 to include Puerto Rico in the amateur draft the following year, far fewer Puerto Ricans were drafted than were regularly signed in the previous era. A steady decline in the number of Puerto Ricans in the major leagues resulted over the next two decades. This is a scenario Dominicans hope to avoid.

From the makeshift baseball diamonds and the manicured fields of baseball academies to the halls of government, Dominicans are all aware of the economic boost the current amateur free-agent system provides to individual families as well as the overall national economy. An international draft would change that and would benefit the few extremely talented prospects who sign six- or seven-figure deals, but would likely lower the overall number of Dominicans signed as well reduce their signing bonuses.

An awareness that went beyond consideration of their own personal benefit is what motivated Latino superstars to stand up for the undrafted, the typically voiceless in the CBA negotiations between the MLBPA and team owners. It is their attention to the implications of the CBA negotiations from a Latino perspective that both motivated their active participation as well as their stance.

It’s a new era.

Featured Image: National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Inset Image: National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum