Legends On A Latino Legend: Paul Casanova

By Adrian Burgos

There are stories that are inside baseball, stories that come straight from the game’s inner sanctum. Those who move within these spaces are aware of the guys who, behind the scenes, make players — and teams — better. They are the anchors and the mentors. And it’s not always the guys in the spotlight. You usually don’t hear about them.

But baseball insiders know Cuban native Paulino “Paul” Casanova — who passed away on Saturday at age 75 — was one of those guys. His decades as a player, coach, and teacher who ran a baseball academy out of his Miami home made him a legend, a mentor to some and a friend to all.

The heart of a teacher

His ability to cajole, encourage and challenge players while providing baseball advice as well as life lessons were the hallmarks of Casanova’s style. The list of those he influenced spans over decades and includes Hall of Famer Phil Niekro, Washington Nationals manager Dusty Baker and Arizona Diamondbacks outfielder J.D. Martínez.

“He’s one of the best people I know,” Martínez told La Vida Baseball. “Casi was much more than a hitting coach; he was a mentor, an example, a friend who will be dearly missed. There’s so much stuff that he would do, I could tell you story after story. Some of the biggest ones in my life.”

“I’ll never forget, when I went to Nova [Southeastern University] and I wasn’t playing well, he showed up at my house and kind of chewed me out. He’d tell me, ‘What are you going to do? Are you going to give up? Are you a quitter?’ He taught me never to quit.”— Diamondbacks outfielder J.D. Martínez

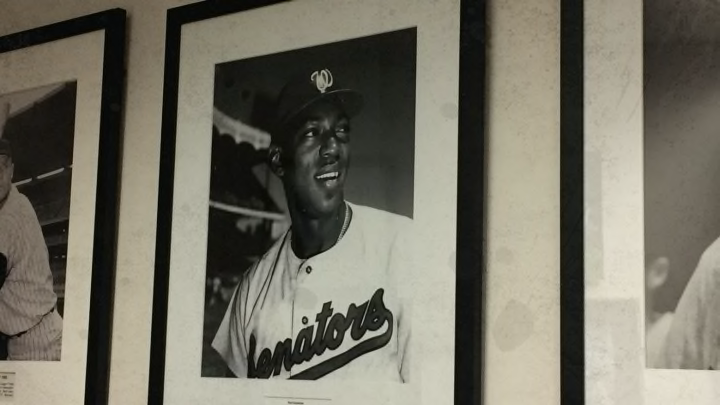

Baker, a teammate of Casanova’s with Atlanta from 1972 to 1974, recalled, “I met Paul when I was a real young player on the Braves. He took me underneath his wing.” Baker proudly shared that “I have his photo hanging on my office wall here in D.C.”

Baker and Casanova, along with Ralph Garr and Hank Aaron, became inseparable. In fact, Baker and Casanova were roommates.

“He used to get on me all the time about taking care of myself, and all the things that a rookie needs to hear,” said Baker, who maybe not coincidentally hit .321 in 1972, his first full season with the Braves and the year that Casanova arrived in Atlanta.

“A really good teacher, there’s no question about that,” said Niekro, who also played with Casanova in Atlanta, winning 20 games for the first time in 1974, Casanova’s final season in the majors.

“When I look back at my career, the first thing that pops up is Paul putting me up on his shoulder [after catching my no-hitter] so that he could carry me off the field. That’s one of my career highlights.”— Phil Niekro, 1997 Hall of Fame

“There’s certain guys when you play baseball, in the clubhouse or when you are on the field, you really feel comfortable being around, and he was one of those guys,” said Niekro, a right-handed knuckleballer who won 318 games over 24 seasons. “And he could talk about anything. … We talked about the good times, the bad times, our growing up [in Cuba and Ohio]. He taught me a lot. … He taught me manners, and how to conduct yourself on the field. I always looked up to him.”

Changing lives with baseball

Paul Casanova lived his life in a manner that captured the credo of Jackie Robinson: “A life is not important except in the impact it has on other lives.”

“Around the neighborhood, if you didn’t have a job or you needed anything, he was always there for you,” said Martínez, who through August 13 was hitting .282/.341/.497 for his career. “He was always the guy that was looking for the next person to help, [even though] he needed help himself. He had bills piling up that he couldn’t even pay.

“He would have kids come and hit, and if the kids couldn’t afford it, he’d let them hit. The workers would be like, ‘We can’t be having all these kids hit without paying. We’ve got bills for us and we’ve got to start charging because we’re going under.’

“If he could get a kid off the street or get a kid to focus, or change a kid’s life, that was the most important thing. That’s all he cared about.

“I remember he would ask me to call kids and talk to them and try to help them and change their lives. He would say, ‘Hey, Flaco [J.D.’s nickname], you think you could call this kid? I think you could really help him out and change him. Just talk to him for me. Please, he really looks up to you.’ I’d say, ‘Ok, Casi.’ He always wanted to help.”

And Casi’s casa was more than a home. It was a baseball academy, a Cuban café and a shrine to the game he loved.

“His camp down there is like the Cuban Hall of Fame and Museum. It’s unbelievable,” Martínez said. “It’s like nothing you’ve ever walked into before. There’s pictures of old-time baseball players everywhere.”

Baker, who made time to visit whenever he was in or near Miami, especially during Spring Training, also remembered the home as a singular gathering place.

“You’d go over to his house and there’d be Minnie Miñoso, Jackie Hernández, Benito Santiago — all the young Latin players.”

For all who made that pilgrimage — names like Orlando Cepeda, Tony Oliva and Luis Tiant — Casanova will be missed.

“He was always positive, loved baseball, and always took a special interest in young players,” said Baker, a three-time Manager of the Year. “I’m going to miss him, big time. It really hurts to know he’s gone. I can’t imagine not hearing his laugh anymore. He was really into helping the Latin players, but he’d help anybody. He’d give you the shirt off his back.”

Featured Image: Dusty Baker / Washington Nationals