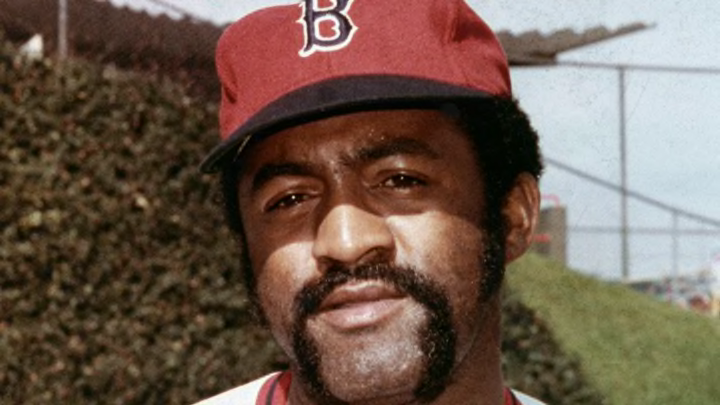

Luis Tiant, his father and a historic first pitch

By Adrian Burgos

The two Luis Tiants standing on Fenway Park pitcher’s mound on August 26, 1975, quickly comes to mind when thinking about baseball and fathers. The image of son holding father’s jacket, ready to start the game. Father soaking in the moment as he hurls a pitch from the mound of a major league park for the first time in three decades.

Their moment didn’t come on Father’s Day. The Tiant’s reunion is nonetheless is a story for Father’s Day. Their story is one of a Latino family that reveals a history of how they dealt with segregation and separation, neither of which could diminish their familial bond nor passion for baseball.

Fenway Park seemed the unlikeliest of places for the Cuban father and son to reunite. The two Luis Tiants had not seen each other in over 14 years. The severing of U.S.-Cuban diplomatic relations in 1961 meant neither would be able to travel to visit the other.

Exiting Cuba

Red Sox fans at Fenway witnessed the elder Tiant throw the ceremonial first pitch before Boston’s 8-2 loss to the California Angels. The game result was not the night’s big story. It was the reuniting of the two Luis Tiants.

Getting Lefty Tiant back on a mound in the U.S. was no easy task. It took a couple of U.S. senators to get Fidel Castro to grant permission for the Tiant parents to travel out of Cuba. The potential normalization of U.S.-Cuban relations during the Jimmy Carter presidential administration provided the opening to advocate for a Tiant family reunion.

Edward Brooke, the first African American elected to the U.S. Senate since Reconstruction, wrote a letter to Castro requesting permission for Luis Tiant’s parent to leave Cuba. His colleague Senator George McGovern carried the letter to Cuba during a May 1975 trip. The letter drew on Castro’s baseball fandom in making the request.

“It is impossible to predict how much longer he will be able to pitch. Therefore, it is hopeful that his parents will be able to visit him in Boston during this current baseball season to see their son unembolden,” Brooke wrote.

In granting Brooke’s request Castro exceeded expectations. The Cuban ruler permitted the Tiant parents to stay for as long as they desired in visiting their son in Boston.

Cuban Aces

Brooke’s interest in the Tiant family reunion was not solely driven by Luis Tiant being one of his Massachusetts constituents. The senator had a personal connection to baseball. Brooke’s uncle was Alex Pompez, an owner in the Negro Leagues who operated out of New York City from 1916 to 1950.

Brooke delivered a eulogy at his uncle’s funeral in March 1974. Seeing friends, family, and former Negro League players at the service for his Cuban-American uncle provided a reminder of the Cubans who were living with the separation caused by the severed U.S.-Cuban relations.

Pompez had signed hundreds of Latinos to play in the Negro Leagues. Lefty Tiant was among the very best. The left-handed pitcher was an ace for Pompez’s Cuban Stars and New York Cubans teams in the 1930s and 1940s. Tiant’s greatest season came in 1947, when he went undefeated with 10 wins for a NY Cubans team that won the Negro World Series.

Dealing with segregation soured Lefty Tiant on professional baseball and life in the United States. He did not encourage his son’s pursuit of a major league career.

The younger Luis Tiant began his professional career in 1959 as an 18 year old in the Mexican League. This enabled him to travel back to Cuba after each season. He faced a difficult choice after the 1961 season when the Cleveland Indians purchased his contract from the Mexico City Tigers.

Concern that Castro’s government would not grant re-entry to those who left to play professionally in the U.S. meant Tiant had to decide between pursuing a major league career or staying in his native Cuba. He chose to pursue his major league dream, leaving his parents behind. They would not see each other until August 1975.

Reunion on the Mound

Luis Tiant enjoyed success early in his big league career with Cleveland as a hard-throwing pitcher. He was forced to learn how to pitch differently after being sidelined with a broken right shoulder in 1970 and other injuries the following year. His road back to stardom was sidetracked twice. The Minnesota Twins and Atlanta Braves organizations released him before he signed with Boston.

Tiant reinvented himself in Boston. He became the right-handed version of his father. No longer possessing the incredible fastball of his youth., he used his baseball intelligence and threw from multiple arm angles and at varying speed to befuddle hitters. The reinvented Tiant became a major league ace, winning 20 games three times and making two All-Star teams with Boston.

Lefty Tiant had only heard secondhand about his son’s success. Communication was limited, and travel between Cuba and the United States virtually nonexistent. The trip to the U.S. would allow the father to witness the son perform on major league mounds he only got to pitch from as a Negro League player.

Luis Tiant had experienced an up-and-down season in 1975. He struggled in the August 26 game against the Angels where his threw the ceremonial first pitch. His parent’s company had a positive impact thereafter. He won three of four decisions in September as the Red Sox claimed the American League East pennant. Tiant was at his season’s best in the playoffs. He won all three postseason decisions versus Oakland Athletics and Cincinnati Reds.

The 1975 Red Sox fell short of their World Series title aspirations. Without Tiant’s performance in his three starts against the Reds, the Red Sox would not have been in position to have their unforgettable Carlton Fisk home run moment. More special, the elder Luis Tiant and his wife Isabel were present to soak it all in. Their pride in watching their son do what the father had been denied by the racial segregation of an earlier era, and their being present when over 30,000 fans at Fenway showered the field with chants of “Lou-ee, Lou-ee” whenever their son stood on the mound, is part of what the emotions of Father’s Day is all about–family, love, and honoring the past.

Featured Image: MLB Photos

Inset Image: Transcendental Graphics