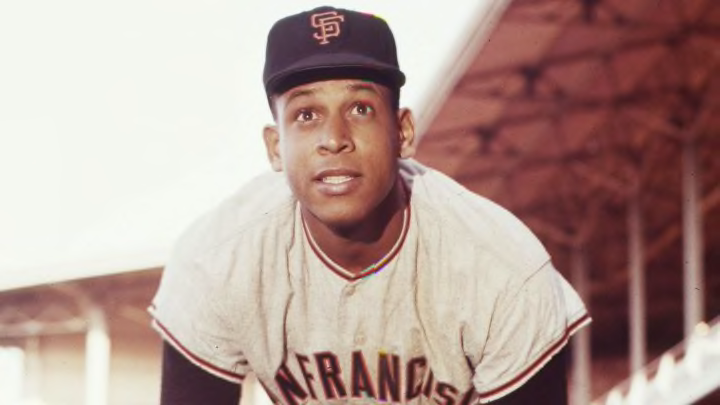

Closing Black History Month with a ‘Cha Cha’ — Orlando Cepeda

When Orlando “Peruchín” Cepeda left for the minor leagues, he was 17. Black. And Puerto Rican.

It was the loneliest of times for a teenager to be away from home.

“We would stop in a small town, and when I got off the bus, I’d be told that I couldn’t enter the place,” Cepeda said.

The year was 1955. Cepeda, tall and gangly, had just signed with the New York Giants for $500. Whether by design or not, they assigned him to the Class D Salem (Va.) Rebels in the Appalachian League.

“We also traveled in station wagons. We would drive six, seven hours. When we stopped to eat, I couldn’t get out,” Cepeda said. “I had to stay inside the vehicle. Colored people weren’t allowed to eat in the establishment.”

Cepeda was the son of Pedro “Perucho” Cepeda, a hard-hitting and hard-living shortstop and first baseman who is arguably one of the greatest players never to reach the major leagues. They called him the “Babe Cobb of Puerto Rico.”

But despite repeated offers from Alejandro “Álex” Pompez, owner of the New York Cubans, Perucho never played in the Negro Leagues, steadfastly refusing to endure the racism and segregation of the times.

Orlando, who had a complicated relationship with his father, finally understood the reasons why, that summer of ’55.

“The white players would stay in the hotel, while I and two other [black players] would have to wait until they found us lodging. Sometimes we slept three to a bed,” Cepeda said.

Surrounded by giants

Cepeda’s journey through the minor leagues was similar to that of other black Latinos in the post-integration era. As we celebrate Black History Month, those stories are worth remembering — and repeating.

For while baseball loves to celebrate pioneers, the game doesn’t always give these particular legends enough credit for overcoming the obstacles and hardships unique to their journeys, preferring to judge them based on the number of major league seasons played and nothing more than cold, hard stats and metrics accumulated.

Cepeda, 80, who is currently in a San Francisco hospital after suffering a recent cardiac event and a resulting fall, talked to La Vida Baseball, in Spanish, just a few weeks ago, and was intent on expressing that while he was lonely in those early days, it turned out he was never alone.

He grew up poor in Puerto Rico, living in rough neighborhoods. But he played sports. Had a doting mother, Carmen Pennes. And the support of many of his father’s ball-playing friends.

“I was raised with baseball,” Cepeda said. “I saw many good players.”

Those “good players” included Satchel Paige, the legendary Negro Leagues pitcher who was a teammate of Cepeda’s father on the Puerto Rican winter league’s Brujos de Guayama and who occasionally watched over the young Orlando. And Josh Gibson, who played with the Cangrejeros de Santurce and is considered one of the greatest players to ever grace the field, a powerful catcher and slugger who was never allowed to play in the majors. In the 1940-41 winter league season, Gibson hit .480 — winning the batting title by 71 points over Willard Brown.

Gibson stood 6-foot-1 and weighed 210 pounds. To Cepeda, he was an intimidating giant.

“I was afraid of him. He spoke English. And I didn’t understand English. I was a kid,” Cepeda said.

Cepeda, who grew up to be 6-foot-2, was surrounded by giants. He was able to watch many major leaguers up close, as clubs traveled to Puerto Rico for exhibitions. He watched the New York Yankees face off against his father and a Puerto Rican all-star team in 1947. And he saw the Brooklyn Dodgers a few years later, featuring fellow Puerto Rican Luis Rodríguez Olmo — and Jackie Robinson.

Wake-up call

In the winter of 1953, Pedro “Pedrín” Zorrilla, the longtime owner of the Cangrejeros de Santurce and a friend of the family, hired Cepeda as a batboy while also allowing him to work out with the team. Orlando went from working a living room full of all-stars to working a lineup full of all-stars.

“Willie Mays. Roberto Clemente. Juan Pizarro. José Pagán. Julio Navarro. We all started out together,” Cepeda said.

Over time, Robinson became Cepeda’s idol.

“Back then, I didn’t know much about racism,” Cepeda said. “At first, I thought Jackie Robinson was just another ballplayer. I didn’t understand his magnitude as a human being or the courage that he possessed.”

A summer in Virginia quickly changed the naive young man’s perspective.

“I went through the same things that Robinson did,” Cepeda said. “It might have been harder for me because Jackie Robinson was an American and I was Puerto Rican. In Puerto Rico, we didn’t have that [segregation].”

A 10-day tryout

Along with segregation came separation. Away from home for the first time and unable to speak English, Cepeda would cry, he once said, “from misery and loneliness.” Before his first game with the Salem Rebels, his father passed away at age 49. Cepeda traveled to Puerto Rico and used his signing bonus for the funeral.

When Cepeda returned to his team, he hit .247 with one home run. The Rebels released him after 26 games.

A Hall of Fame career almost ended before it had even started. As was the case for many Latino pioneers along their journeys, a guardian angel appeared at the most opportune moment. Zorrilla, who for all intents and purposes had become Cepeda’s second father, was good friends with a winter league umpire who happened to own the Class D Kokomo (Ind.) Giants of the Mississippi-Ohio Valley League.

“When the Giants released me, I wanted to return to Puerto Rico,” Cepeda said. “Pedrín called the owner, and he said, ‘No, tell him to come here. I’ll give him $100 for 10 days.’

“If Pedrín hadn’t gotten involved, I probably wouldn’t have [made it]. You always need a helping hand. But one person is enough to make a difference.”

Cepeda was fortunate to have more than one benefactor. Given a second chance at Kokomo, he flourished under the direction of manager Walt Dixon, a white North Carolinian and a career minor leaguer. Cepeda lasted more than 10 days, hitting .393 in 92 games with 23 doubles, 21 home runs and 91 RBI.

Guided along the way

So many years later, Cepeda remembers Walt Dixon as a symbol of the goodness to be found in people.

“However bad a situation is, you always encounter good people. I remember Walt Dixon with a lot of fondness because he was the one who helped me,” Cepeda said. “Out of 100 people, 99 might tell you ‘no,’ but there’s always one who will say ‘yes.’ And that’s the person who will help you. And he helped me a lot.

Dixon provided simple, near-fatherly guidance to the 17-year-old.

“Walt had faith in me. He would pick me up at home and take me to the ballpark. And after the ballpark, he would take me back home.

“In my first game, I batted eighth. I struck out three times. He told me, ‘You are going to be a good ballplayer. From now on, you’ll hit fourth and you’ll play every day.’

His affection for Dixon is still palpable.

“Walt Dixon said that he saw that I had talent. If one person loves you, that’s enough. And I was fortunate that he helped me mucho, mucho, mucho [a lot]. And for that I’m very grateful.”

Cepeda was grateful to one more person that first season. With integration and the demise of the Negro Leagues, Pompez had become a scout. He was never able to sign the elder Cepeda for the Cubans, but he helped secure the son for the Giants after a tryout in Florida.

“If it hadn’t been for him, the first year would have been very difficult,” Cepeda said.

Hall of Fame career

Cepeda never stopped hitting after his stint with the Kokomo Giants. In the span of three years, he jumped from Class D to Class C to Triple-A. When the Giants moved to San Francisco in 1958, they debuted Cepeda as their first baseman.

Cepeda was voted Rookie of the Year, averaging .312 with 25 HR and 96 RBI while leading the National League with 38 doubles. He won the hearts of San Francisco’s major league fan base as it first came into bloom, earning the name “Cha Cha” and “Baby Bull.”

Despite knee injuries, he played at a Hall of Fame level for most of his 17 seasons in the majors. In 1961, he hit .311 with 46 home runs and 142 RBI, becoming the first Latino to lead a league in both HRs and RBI. In 1967, he hit .325 with a league-leading 111 RBI while being voted the NL MVP and helping the St. Louis Cardinals win the World Series. Cepeda was elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum in 1999 by the Veterans Committee.

Think about that: Without the unlikely trinity of Zorrilla, Dixon and Pompez, one of the greatest Latino sluggers ever might have never concluded his journey and accomplished his destiny.

“I always think of them,” Cepeda said. “They were different people. Walt was a white American. Pedrín was Puerto Rican. Pompez was Cuban-American from Tampa. But they were special people.

“No one is born alone,” Cepeda added. “If one person takes interest in you, that’s enough. That was my case.”

Featured Image: Transcendental Graphics / Getty Images Sport

Inset Image: Bettman