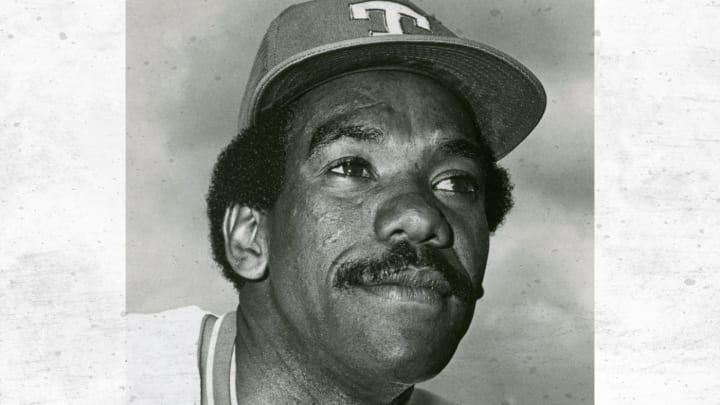

Remembering Rogelio Moret

By Frank Andre Guridy

On a warm night in Arlington Stadium forty years ago, Rogelio Moret, the fireballing left hander for the Texas Rangers, was summoned from the bullpen by manager Billy Hunter to protect a 3-1 lead in the top of the sixth inning of an early regular season game against the New York Yankees. In the days leading up to this appearance, Moret had repeatedly expressed unhappiness with the Rangers and demanded to be traded. But on this night, the slender southpaw put his feelings of unhappiness aside and unleashed his fastball at the defending world champion Yankees. He went on to earn a save by pitching four effective innings of four-hit, one run ball to help the Rangers defeat the Yankees 5-2.

But all was not well with the man known as “El Látigo” (the Whip), a nickname he earned from fellow Puerto Rican Willie Montañez who claimed he could hear Moret’s blazing fastball snap across the plate.

Two days later, as his teammates took batting practice before a game against the Detroit Tigers, he stood frozen in the Rangers clubhouse with a blank stare and his right arm extended, holding a shower shoe in a “catatonic trance” for almost 90 minutes, refusing to acknowledge anyone who tried to talk to him. Hours later, he was sedated with multiple injections and taken to the Arlington Neuropsychiatric Center where he was treated for schizophrenia over the next few weeks. He was eventually released by the Rangers, but he was never able to get his baseball career back on track.

Living the Life

For Latino players, La Vida Baseball is as much a story of struggle as it is triumph. While we rightly celebrate of the extraordinary achievements of Hall of Famers, such as Roberto Clemente, Juan Marichal, Pedro Martínez and the success of today’s All-Stars like José Altuve, we might also remember the many more who never overcame the structures of racism and cultural illegibility that mark the Latino experience. The story of Rogelio Moret Torres, known in the U.S. baseball world as “Roger Moret,” vividly illustrates the structural and personal manifestations of those struggles.

During his 12-year professional baseball career, the moments of brilliance he displayed on the pitcher’s mound were overshadowed by his struggles with mental illness, a fact that the Major League Baseball establishment was unable and unwilling to accommodate. Eventually, he was cast aside and treated like damaged goods when he could no longer perform on the baseball diamond. His struggles with mental illness continued in the decades after his Major League career ended in 1980.

Moret’s story is at once unique and representative of Latinos who labor and live in the United States. He endured the customary humiliation of those who have had their names Anglified. In baseball, “Rogelio” became “Roger,” a pattern of misnaming that continues even in recent accounts of his life. And throughout his career, Rogelio found himself performing in places that were not the most welcoming environments for Black players from Puerto Rico. In the Minors, he played for teams in Waterloo, Iowa; Winter Haven, Florida; and Louisville, Kentucky. During his Major League career, he pitched for the Boston Red Sox, the Atlanta Braves, and the Texas Rangers, franchises located in cities with their own histories of racism.

Red Sox Swingman

Born in Guayama, Puerto Rico, the lanky 6’ 4’’, 170-pound left-hander was signed by the Boston Red Sox out of high school in 1968. Over the next few years, he was shuttled between the Minors and Majors before he made his breakthrough in 1973, when he reeled off 11 straight wins as a reliever and spot starter for Boston. He finished the year with a 13-2 record and he was touted by baseball observers as a rising star and a “swingman” who could either pitch long innings in relief or make spot starts. In 1973, Moret amassed 156 innings in 30 appearances, only 15 of which were starts.

After a subpar 1974 season, he came back with another great year in 1975 with a 14-3 record and he helped Red Sox win the 1975 American League pennant. The memorable team led by All-Stars like Luis Tiant and future Hall of Famers, Carl Yastrzemski, Carlton Fisk and Jim Rice also benefitted from the overlooked contributions of Rogelio Moret.

But his tenure with the Red Sox was marred by incidents that were ignored or dismissed as bad behavior by a less than intelligent Puerto Rican when it was clear to some, even then, that these incidents were manifestations of Moret’s fragile emotional state. During his time in Boston, he had a number of off-the field incidents, including crashing his car into a stalled truck on a highway.

The Road to Texas

After the Red Sox fell short of winning the 1975 World Series against Cincinnati, team brass had seen enough and traded Moret to the Atlanta Braves in December. The next year in Atlanta, he continued to struggle, and this time it affected his on-field performance. At one point, the Braves sent him home for five weeks to address “family problems.”

Atlanta traded Moret to the Rangers after the 1976 season. Now with his third team in three seasons, Moret injured his shoulder and only pitched in 18 games during the 1977 season. The next spring, Moret repeatedly announced to the press and team management that he wanted to be traded away from the Rangers. It was in this context that the “shower shoe” episode occurred on April 12, 1978.

The Moret affair is often remembered as a singular incident, but his nervous breakdown was one of many meltdowns that occurred on a baseball team embroiled in constant turmoil.

The Rangers, then owned by the volatile Brad Corbett, were a dysfunctional franchise. Though he liked to portray himself as a “player’s owner,” Corbett turned over the team’s roster repeatedly in an impatient attempt to make the Rangers winners. Corbett had a penchant for his own emotional outbursts when his team did not perform up to his expectations. He also hired and fired managers at will and they, in turn, resented their roles of managing players who were making more money in the new era of free agency.

In short, the Rangers were not exactly an ideal situation for a Puerto Rican pitcher who was struggling with his own personal demons.

Troubled Times

Playing Major League Baseball remained an isolating experience for many Latino ballplayers thirty years after Jackie Robinson broke the color line in 1947. The Latino player of the 1970s continued to endure many of the same struggles that the first generation of Latino integration pioneers had in the 1950s and 60s. While some were lucky enough to play on teams with significant numbers of Latinos on their rosters, such as the Pittsburgh Pirates or the San Francisco Giants, most found themselves as numerical minorities on teams that were indifferent to the challenges they faced as Blacks and Latinos in a foreign environment.

The isolation and alienation Latinos continued to endure was spotlighted in a Los Angeles Times story during the summer of 1979. Moret’s Dominican teammate Nelson Norman on the Rangers told the Times, “they don’t tell you it will be any different than where you are from. They try to sell you something so they don’t warn you on how rough it will be.” In the same story, then Mets first baseman Willie Montañez told the Times: “Sportswriters ignore us out of habit. They back away from athletes who are different.”

“Sportswriters ignore us out of habit. They back away from athletes who are different.” — Mets first baseman Willie Montañez

And we should not forget that the Chico Escuela stereotype was born on the Saturday Night Live television show (“Beisbol has been bery bery good to me”) in this period, illustrating the cultural isolation and exclusion many Latinos felt in this decade.

Thus, Moret’s breakdown in the Ranger clubhouse forty years ago is more than a story of a troubled “loner.” Rather, it can be viewed as an act of self-advocacy in a period when many in his generation of Latino players were disregarded and treated as subhuman.

The masculine world of Major League Baseball had proven unwilling to reckon with the complexities of mental illness. In the 1950s, the emotional struggles of white centerfielder Jimmy Piersall’s were acknowledged and popularized by Fear Strikes Out, the Hollywood movie, based on his memoir. But Black and Latino athletes did not receive equivalent sympathy from fans or baseball writers.

In 1970, Alex Johnson a gifted hitter, won the American League batting title. But after Johnson, an African-American, behaved erratically on the field and in the clubhouse, the Angel fans of white suburban Orange County and the press harangued the troubled outfielder without mercy. The Angels suspended him without pay, but thanks to the advocacy of Major League Baseball Players’ Association head Marvin Miller, the team was forced to reinstate Johnson with back pay after Miller successfully sued the team for refusing to treat Johnson’s mental illness like it did physical injuries.

Though Rogelio Moret received some sympathy from the press and fellow players, he was solely dependent on the goodwill of general managers whose primary concern was his value on the field. Piersall received understanding—and continual employment in baseball after retirement—while Moret and Alex Johnson did not.

As we look forward to seeing our peloteros excel on the diamond this season, we might also recall the struggles of the many more who did not overcome the racism and cultural illegibility that profoundly shape the experience of Latino players—and all Latinos–to this day.

Featured Image: Texas Rangers

Inset Image: Topps