Whose game is it, anyway?

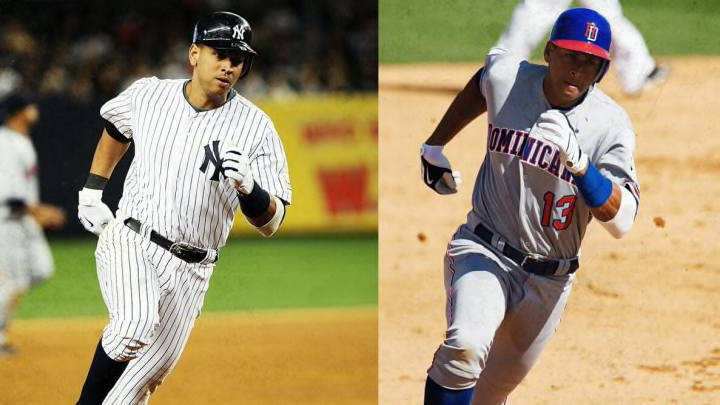

The United States or la República Dominicana? The country of your birth or la madre patria? This not-so-simple decision for whom to play in the World Baseball Classic bewitched Álex Rodríguez, born in New York City to Dominican parents.

In 2006, he first demurred and then suited up for the Stars and Stripes, earning criticism and even scorn. In 2009, after proclaiming that he was fulfilling his mother’s dream, he switched to the Dominican Republic and joined Big Papi on the big stage, only to lose twice to the Netherlands in the first round.

Of course, everything with A-Rod is complicated. But his choice cloaks broader questions about baseball when it comes to many Latinos. Where do we fit in? How should we play the game?

Whose game is it, anyway? The game we grew up with? Or the game we came here to play?

America’s Global Game

There’s no simple answer. Look at the WBC results to date: Japan won the first two titles and the Dominican Republic, without A-Rod, took the 2013 edition. Dare I say, it’s everyone’s game.

While baseball evolved gradually in the United States, pelota in Latin America and yakyū

in Japan took root in an advanced form around the time the National League was born in 1876. The game quickly adapted to foreign soils. The Japanese culture has always emphasized Wa, or togetherness, along with the sacrifice bunt. Fans there don’t boo managers or strategy. And, by the way, Sadaharu Oh hit 868 home runs. The U.S. doesn’t have a monopoly on sluggers.

Back in Cuba, professional play began in 1878. The game was considered a revolutionary sport long before Fidel Castro came to power — those loyal to Spain preferred jai alai, but those who fought for independence played base ball, as it was spelled back then.

The Fan Experience

That feisty spirit lives on today in Havana’s La Esquina Caliente, or Hot Corner, the city plaza where fans gather daily to debate each other about their favorite stars and teams. That chippy attitude is why it shouldn’t be surprising that most Latinos not named Albert Pujols play with a certain bravado, swinging mightily at pitches down at their ankles or above their shoulders.

In Cuba, the music goes full blast during the bottom of the inning, when the home team is at bat. “The big difference is culture around game and life in the stands,” says La Vida Baseball contributor Peter C. Bjarkman, an expert on Cuban baseball who travels to the island almost annually. “The fans are there to interact.”

In Mexico, you’ll eat tacos al pastor, hear mariachi bands and see fans sporting colorful lucha libre masks. In Puerto Rico, less horns and more percussion. The Dominicans prefer merengue and serve empanadas. Everything is spontaneous and seemingly disorganized, set to soaring riffs into the night.

In a sport in which one-third of the players now come from abroad, it’s about assimilation versus acculturation, metrics be damned. Bilingual and bicultural, Latino players choose in what language and in what manner they live the moment. Drake for the walkup song; mofongo relleno or sope con carne for the postgame meal.

A Passion Play

Not everyone wants to admit it, sometimes not even Latino players themselves, but America’s Game has become the Americas’ Game. A passion play, showcased through megaphones, cheerleaders, dancers, cowbells, snare drums and full-fledged orchestras.

And some non-Latinos, like Bryce Harper, play to the beat. He’s the poster child for a new generation of Anglo players who have embraced the Latin way of playing — with passion and fury. A new kind of assimilation at work.

“Latinos bring music to the game,” says Vladimir Guerrero, the Dominican outfielder who was quite the showman with his bat and glove during 16 major-league seasons, swinging at pitches that bounced two feet in front of the plate and throwing bombs from right field — regardless of whether the runners were going.

So, unless the United States finally wins the World Baseball Classic this month, we don’t need a third-string catcher lecturing us every summer on the right way to play. Or, worse, Rougned Odor of Venezuela sucker-punching a fellow Latino, Dominican José Bautista, over the supposed crime of a bat flip. Different styles make for a more fully realized game of baseball.

It’s our game, everyone’s game.

Featured Images: Nick Laham / Getty Images Sport / and Ronald C. Modra / Sports Imagery / Getty Images Sport